CDC Reports Infection as a Major Cause of Maternal Death

May 14, 2019

A report issued on May 10, 2019, by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) indicates that every year, about 700 mothers in the United States die of pregnancy-related or post-pregnancy complications. About one-third of the deaths occur during pregnancy and the rest up to one year after delivery, called the post-partum period. Of these, approximately three in five were preventable, the authors wrote.1

Almost 4 million babies are born in the U.S. every year.2 Most often, both mother and baby (or babies) are healthy, but this isn’t always the case. Aside from those who die, some mothers experience complications that leave behind lasting consequences, such as amputations, chronic pain and fatigue, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and more.

According to the CDC, the leading causes of death among pregnant or post-partum women are cardiovascular conditions (more than 33% of deaths), infection (12.5% of deaths), and hemorrhage (11.2% of deaths). Infection can occur any time in the pregnancy and post-partum periods, but the first 6 days following delivery is the period when the highest number of infections occur.

Saying that a woman died from an infection isn’t the whole story, however. If you die from infection, you die from sepsis. Sepsis is the body’s overwhelming and life-threatening response to infection that can lead to tissue damage, organ failure, and death. It is your body’s overactive and toxic response to an infection. These findings issued in the May 2019 report indicate that sepsis is a major factor in pregnancy and post-partum deaths in the U.S.

Complications Related to Sepsis

Out of every 10,000 live births each year in the U.S., 4 to 10 mothers are touched by sepsis. Aside from the risk of death to both mother and child, pregnant women who develop infections that trigger sepsis are at increased risk of delivering prematurely and having a prolonged recovery following delivery.3

Risk Factors for Maternal Sepsis

Any woman who is pregnant, recently had a miscarriage or abortion, or delivered a baby can contract an infection that could lead to sepsis. Some women are at higher risk for developing sepsis. These include women who:3

- Are pregnant for the first time

- Are Black

- Have no insurance or use public insurance

- Had a Cesarean section

- Became pregnant with the help of reproductive technology

- Delivered multiples (twins, triplets, or more)

Women with chronic diseases such as lupus, diabetes, heart disease, or liver disease are also at higher risk.

The Challenges in Recognizing Sepsis

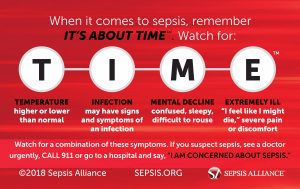

As part of sepsis awareness outreach, the public is encouraged to learn the memory aid TIME:

Unfortunately, this can be challenging in this group. Changes that occur in a woman’s body while she is pregnant or after delivery or miscarriage can mask sepsis symptoms. She usually needs to urinate more often because of the pressure the baby puts on her bladder, but frequent urination is also a symptom of a urinary tract infection. Her heart beats faster, her blood pressure may drop, and she may breathe more quickly than normal after delivering. Women may continue to have pain, or feel light-headed after giving birth, and feeling chilled or sweaty after delivering a baby are all normal reactions. These are all possible signs of sepsis too.

So, how can a woman tell if what she is experiencing is normal or something much more serious? Generally, the discomforts a woman feels after delivery gradually decrease until they go away. If you are experiencing any of the symptoms listed above and you think they are getting worse, not better, call your doctor. If the symptoms are severe, call 911 or go to the closest emergency room and ask, “Could this be sepsis?”

To learn more about maternal sepsis, what to watch for, and how to prevent infections, visit Sepsis and Pregnancy & Childbirth, part of the Sepsis and… library. And learn more about the Sepsis Alliance award-winning It’s About TIME™ campaign.

[1] Petersen EE, Davis NL, Goodman D, et al. Vital Signs: Pregnancy-Related Deaths, United States, 2011–2015, and Strategies for Prevention, 13 States, 2013–2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2019;68:423–429. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6818e1

[2] Births and Natality. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/births.htm. Accessed May 13, 2019.

[3] Plante LA, Pacheco LD, Louis JM. SMFM Consult Series #47: Sepsis during pregnancy and the puerperium. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;220(4):B2-b10. https://www.ajog.org/article/S0002-9378(19)30246-7/fulltext